Jia Zhangke’s Caught by the Tides plays the AFS cinema through this thursday, JUNE 5th. to mark its austin theatrical run—co-presented by our very own AAVClub—aaaff programmer josh martin offers his in-depth look at the film and its long history.

At a recent festival panel, representatives of two European distributors for Caught by the Tides discussed their experiences with the film. Both agreed that it posed a challenge, even by Jia Zhangke’s far-from-mainstream standards, and required special handling on the marketing and distribution fronts. As though to emphasize its “specialness,” the film was Jia’s first to release in Italy exclusively in the original version with subtitles, on the grounds that anyone who bases viewing decisions on the availability of an Italian dub would never watch it anyway.

I don’t question the choices of distributors with years of experience in foreign markets I know nothing about. But even if we grant the conventional wisdom—that Jia’s newest outing is mainly for the advanced students—we can still ask why. The prevailing answer is purely descriptive: Caught by the Tides is an assemblage of material shot over a 22-year period, from 2001 to 2023; the main storyline, excepting its final section, is repurposed footage from three of Jia’s previous features, Unknown Pleasures (2002), Still Life (2006), and (to a much lesser extent) Ash Is Purest White (2018). Some has been retrieved from the cutting-room floor, like a strange homoerotic subplot dropped from the final edit of Still Life, but much of it appeared verbatim in the earlier films.

There’s no point arguing that viewers of Caught by the Tides who have watched this material in its original contexts will have a different response from those seeing it for the first time. But I’m not convinced there are any special insights here accessible only to those who remember, say, the opera scene from Unknown Pleasures. For the uninitiated, knowing this story was largely cobbled together from preexisting footage might usefully account for the other oft-cited challenge of Caught by the Tides—its fragmented, elliptical quality—but this rests on its own questionable assumptions, since Jia says his first cut yielded a tighter, more conventionally robust narrative at odds with what he was going for.

The story at which he finally arrived essentially concatenates the plots of the three earlier films, or at least key elements thereof. At its 2001 outset, Zhao Qiaoqiao and Guo Bin (played respectively by Jia’s longtime collaborators Zhao Tao and Li Zhubin) are in Datong, a smallish city in Jia’s native Shanxi province. Qiaoqiao is a dancer/model who works nightclubs and marketing events, managed by her callous boyfriend Bin. As their relationship deteriorates, Bin leaves to pursue opportunities elsewhere, promising to send for Qiaoqiao later. In 2006, she tracks Bin to Fengjie, on the rural outskirts of Chongqing, where he’s engaged in shady dealings around the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. When the two finally reunite, one of them—probably Bin, but it’s not entirely clear—puts an end to the relationship. Sixteen years later, a laid-off Bin again strikes out for greener pastures, only to wind up back in Datong.

Many accounts sum this all up as a “love story,” a label seemingly supported by the Chinese title Fengliu Yidai: “A Romantic Generation.” But “romantic” is a variegated term in Chinese as in English, and is less apt here in interpersonal terms than as a way of life untethered from convention and the ordinary—whether by choice or by the ceaseless shifts in China’s social and economic terrain, conveyed all the more effectively by the use of actual period footage. What Qiaoqiao and Guo Bin feel for each other at any given point is less important than how they change, and what this says about their times. Qiaoqiao attains a degree of independence once far beyond reach for most Chinese women, but by the story’s end, this has yet to make much difference to her economic outlook. Guo Bin is adrift and physically infirm, reflecting Li Zhubin’s real-life stroke that was previously fictionalized in Ash Is Purest White (with Liao Fan as the Guo Bin character); he also sees a former underling put his talent-agent experience in the shade, achieving far greater success with a dancing TikTok star than Bin ever did with Qiaoqiao. Bin thus becomes another of Jia’s small-time hustlers who can’t keep pace with the changes around them, a line stretching back to the title character of Xiao Wu (1997).

But to focus on Qiaoqiao and Guo Bin is to neglect how much of Caught by the Tides is comprised of documentary material. Some is seamlessly integrated with the staged footage of Zhao, Li, et al., while some plays out as long tangents with little clear relevance to the fictional narrative. But as someone who thinks Jia’s storylines can be a mite overdetermined—a perception admittedly colored by his tendency in interviews towards platitudes about “the resilience of the Chinese people”—I found these digressions refreshingly off-the-cuff, even when fraught with unsubtle significance in their own right (e.g. the man who took over an aging “Workers’ Cultural Palace” and rescued a Mao portrait from its woodpile). At times, most conspicuously the initial 2001 sections, the film feels like a documentary with fictional interludes instead of the other way around, for good reasons rooted in its decades-old origins.

In 2001, Jia acquired a DV camera and began shooting things around him with no particular end in mind. He soon reconceived these excursions as a long-term project dubbed The Man with a DV Camera, a title dropped once he started incorporating material on additional formats like HD, 16mm, and 35mm. Some of the footage made its way into other films, as Jia repeatedly skirted the line between documentary and fiction: his doc short In Public (2001) is practically an extended trailer for Unknown Pleasures, and the documentary Dong led directly to Still Life, shot in many of the same locations with some of the same cast. In 2020, a locked-down Jia reviewed the footage—“precious memories” in which he now saw “archeological significance”—and decided the time had come to wrap up the erstwhile Man with a DV Camera. He finally did so in 2023, with the last pickup shots for Caught by the Tides.

Jia Zhangke (second left) filming Unknown Pleasures, circa 2001…

Jia’s latest, then, is best understood not as a repurposing/cannibalization of earlier projects but as the realization of one of his earliest. Jia consciously worked some of his interim narratives into the grander design: he claims his characters’ recycled names and similar attire were originally down to pure laziness, but by Still Life he was taking deliberate steps to match footage across different projects. Despite this, he had no overarching plot before the pandemic-era review, and it’s fair to ask why he chose that particular moment to bring it all together. The obvious answer, given by Jia himself, is that the pandemic formed a clear historical demarcation, much as the upheavals of 1989 supplied the cutoff for 2000’s decade-spanning Platform.

…and Caught by the Tides two decades later

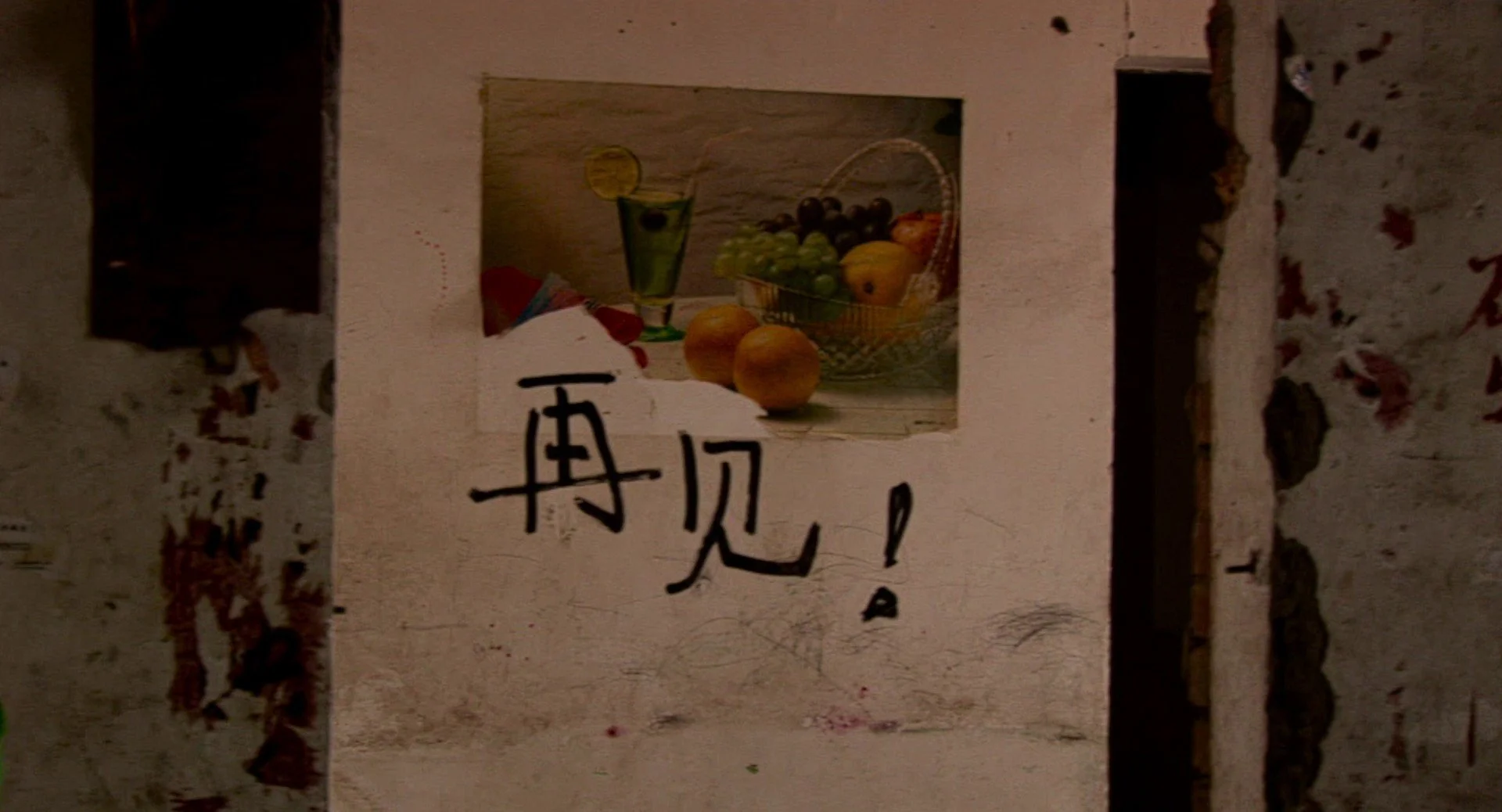

The penultimate scene of Caught by the Tides, between Qiaoqiao and a service robot in an eerily depopulated supermarket, evinces special interest in the technological side of what Covid hath wrought, or at least accelerated. It also caps a theme running throughout the fictional narrative, of human interaction increasingly mediated by technology: almost all of Qiaoqiao’s dialogue is delivered through text messages displayed as intertitles, and Zhao Tao doesn’t speak a single word in the entire film, although she does sing and shout. Jia attributes this to his rediscovery of “the power of silence” while watching the old footage, and Zhao’s performance is consonant with her longstanding reputation as an expressive actor in the silent-era mold—in fact, she already gave a silent performance in 2010’s I Wish I Knew. But this non-verbal expressiveness becomes a liability as the years go on and in-person socialization (in dance clubs, karaoke rooms, etc.) gives way to SMS, social media, and automation, and whatever small comfort can be taken from the service robot’s sympathetic programming—it “reads” the sadness in Qiaoqiao’s face, at least once she removes her mask—is tempered by the fact that it can only respond with canned “inspirational” quotes of doubtful relevance.

Jia is no luddite, as evidenced by his early embrace of DV/HD and his involvement with Do Not Answer, an odd science-fiction talk show set in the Three-Body Problem universe, wherein “Future Research Division Chief” Jia Zhangke interviews guests on topics like space travel and virtual actors. (He’s also directed a six-minute film for Kling AI, which is as inessential as pretty much all of his commissioned shorts.) But there’s more than a note of ambivalence to the brave new world of Caught by the Tides, and more possible clues to Jia’s mindset can be gleaned from a look back at his 2003 article “The Age of Amateur Cinema Will Return.” A manifesto for the then-burgeoning ranks of low-budget, DV-equipped filmmakers, this short essay denounced the homogenizing effect of “so-called professional filmmakers” who “caution themselves against any amateur act that breaks the established classical rules,” leaving only “rigid concepts and preexisting prejudice.”

Much of Jia’s piece still resonates today, but its ideal of an emergent “amateur cinema”—the one that animated the Man with a DV Camera project—reads as outmoded when everyone has a video camera in their pocket and an act as amateurish as the viral “Dschinghis Khan” video in Caught by the Tides can form a lucrative profession. Another reason, then, for Jia to call time on an undertaking that spanned nearly his entire career to date and plausibly informed every film he made in the meantime. Not for nothing has he described Caught by the Tides as a “farewell work,” averring that he has no plans to retire (despite some pandemic-era musings to the contrary). What comes next for Jia, as he tinkers with AI while professing “panic” at its potential impact, is probably unknown even to himself. Per recent comments, he could finally move ahead with In the Qing Dynasty, a long-gestating martial-arts period drama co-produced by Johnnie To; then again, he could well jump to one of his parallel career tracks as an actor, festival head, restaurateur, talk-show host, or sometime deputy to the National People’s Congress. These sometimes baffling incongruities are part and parcel of what Jia Zhangke has been since he controversially left the underground with The World (2004) to join China’s state-supervised film sector: a filmmaker who won’t consistently go against the flow, but will at least try to shape its direction.